Behold! I just finished painting the complete set of Talisman Timescape miniatures, beautifully sculpted by Trish Morrison and released by Citadel in 1988.

Talisman is a strange board game -- especially the classic version released by Games Workshop in the 1980's (aka the 1st and 2nd editions of Talisman). I don't think I properly understood Talisman until I read an essay written by Umberto Eco (the author of The Name of the Rose) about the movie Casablanca (the 1942 film with Humphrey Bogart). Random? Probably. But stay with me and I promise to post most more pictures of miniatures.

The essay is in Eco's book How to Travel with a Salmon (1995) and is itself titled "Casablanca, or, The Clichés Are Having a Ball". In it, Eco meditates on the incredible success of Casablanca. He writes that this success is surprising since the movie is riddled with hundreds of clichés: the faithful servant, the doomed lover, the redeemed drunkard, the hooker with a heart of gold... Normally, one or two clichés are enough to turn a good work of art into a bad one. But the beauty of Casablanca is that it boasts so many clichés that they reach a critical mass that pushes the movie beyond mere badness, transforming it into something immortal. As Eco writes:

Two cliches make us laugh. A hundred cliches move us. For we sense dimly that the cliches are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion. Just as the height of pain may encounter sensual pleasure... so too the height of banality allows us to catch a glimpse of the sublime.

By piling on all these clichés culled from other stories and other movies, Casablanca allows us to relive all these prior experiences at once -- in one delightful, headlong rush.

And this is exactly what Talisman does. The beauty of the game is that it takes every single cliché, trope and archetype from the world of fantasy and crams it into one box. A princess? Check! Gaming against Death? Check! The Black Knight guarding a bridge? A life stealing rune sword? The Holy Grail? A dungeon crawl? A torture chamber? A bare chested barbarian? Check! Check! Check! The end result is a game that exists in every fantasy world at the same time: partly Tolkien, partly Warhammer, partly historical, partly Moorcock, partly Robert E. Howard and partly the Bros. Grimm. Adding just one or two of these elements would make the game seem a little goofy. But throwing them all together? Well that's an act of genius.

And what I love about Timescape is that the lads at Games Workshop found a way to crank this bastard up to 11. After all, there's no reason to limit oneself to the realm of fantasy. Using the thin premise of an inter-dimensional portal bridging the world of Talisman with the future, Timescape opens up a universe of new possibilities. Why not throw in as many figures from science fiction as possible? Predators, Dune worms, Time-lords, Terminators all appear in thinly disguised forms. Add to them Warhammer 40K characters (Space Marines, Astropaths), generic sci-fi figures from central casting (The Scientist! The Space Pirate!) and (like a maraschino cherry on top) Indiana Jones.

The end result is a hot frothy mess of goodness. The fact that the game is hilariously unbalanced barely matters. Who doesn't want to send a Space Marine rampaging across the fields and woods of a fantasy world, armed with the Holy Lance and accompanied by a Poltergeist? Why not give your Samurai a jet pack and a power glove? Why not give the Chainsaw Warrior one last shot at glory?

|

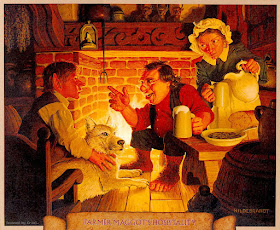

| H.R. Giger, H.G. Wells and Frank Herbert rock out. |

I've certainly enjoyed the latest edition of Talisman published by Fantasy Flight Games. But after playing both the old Talisman and the new a number of times, I've realized that I prefer the original -- mainly because Fantasy Flight's version attempts to unify the look and feel of the game, adding game balance and smoothing out the rough edges so that it presents a somewhat cohesive world. This seems sensible. But screw sensibility with a spoon. It's precisely the chaotic mish-mash that makes Talisman so much fun, especially with the delirium of Timescape in the mix. As Eco would say, all the clichés are having a ball.

Anyway, I hope you enjoy the pics!

Talisman Timescape Archaeologist

Talisman Timescape Astronaut

Talisman Timescape Astropath

Talisman Timescape Chainsaw Warrior

Talisman Timescape Cyborg

Talisman Timescape Scientist

Talisman Timescape Space Marine

Talisman Timescape Space Pirate

Thanks for looking!